- Photo Safaris

- Alaska Bears & Puffins World's best Alaskan Coastal Brown Bear photo experience. Small group size, idyllic location, deluxe lodging, and Puffins!

- Participant Guestbook & Testimonials Candid Feedback from our participants over the years from our photo safaris, tours and workshops. We don't think there is any better way to evaluate a possible trip or workshop than to find out what others thought.

- Custom Photo Tours, Safaris and Personal Instruction Over the years we've found that many of our clients & friends want to participate in one of our trips but the dates we've scheduled just don't work for them or they'd like a customized trip for their family or friends.

- Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour December 2017 -- with Angkor Wat option

- Reviews Go hands-on

- Camera Reviews Hands-on with our favorite cameras

- Lens reviews Lenses tested

- Photo Accessories Reviews Reviews of useful Photo and Camera Accessories of interest to our readers

- Useful Tools & Gadgets Handy tools and gadgets we've found useful or essential in our work and want to share with you.

- What's In My Camera Bag The gear David Cardinal shoots with in the field and recommends, including bags and tools, and why

- Articles About photography

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Travel photography lesson 1: Learning your camera Top skills you should learn before heading off on a trip

- Choosing a Colorspace Picking the right colorspace is essential for a proper workflow. We walk you through your options.

- Understanding Dynamic Range Understanding Dynamic Range

- Landscape Photography Tips from Yosemite Landscape Photography, It's All About Contrast

- Introduction to Shooting Raw Introduction to Raw Files and Raw Conversion by Dave Ryan

- Using Curves by Mike Russell Using Curves

- Copyright Registration Made Easy Copyright Registration Made Easy

- Guide to Image Resizing A Photographers' Guide to Image Resizing

- CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson

- Profiling Your Printer Profiling Your Printer

- White Balance by Moose Peterson White Balance -- Are You RGB Savvy by Moose Peterson

- Photo Tips and Techniques Quick tips and pro tricks and techniques to rapidly improve your photography

- News Photo industry and related news and reviews from around the Internet, including from dpreview and CNET

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Resources On the web

- My Camera Bag--What I Shoot With and Why The photo gear, travel equipment, clothing, bags and accessories that I shoot with and use and why.

- Datacolor Experts Blog Color gurus, including our own David Cardinal

- Amazon Affiliate Purchases made through this link help support our site and cost you absolutely nothing. Give it a try!

- Forums User to user

- Think Tank Photo Bags Intelligently designed photo bags that I love & rely on!

- Rent Lenses & Cameras Borrowlenses does a great job of providing timely services at a great price.

- Travel Insurance With the high cost of trips and possibility of medical issues abroad trip insurance is a must for peace of mind for overseas trips in particular.

- Moose Peterson's Site There isn't much that Moose doesn't know about nature and wildlife photography. You can't learn from anyone better.

- Journeys Unforgettable Africa Journeys Unforgettable -- Awesome African safari organizers. Let them know we sent you!

- Agoda International discounted hotel booking through Agoda

- Cardinal Photo Products on Zazzle A fun selection of great gift products made from a few of our favorite images.

- David Tobie's Gallery Innovative & creative art from the guy who knows more about color than nearly anyone else

- Galleries Our favorite images

Myanmar: History and Highlights of a changing country

Myanmar: History and Highlights of a changing country

Submitted by David Cardinal on Mon, 11/12/2012 - 16:18

After the recent easing of sanctions by the U.S. government and moves toward greater political inclusiveness and democratization, Myanmar is back as a tourist destination for many Americans who were put off by the sanctions (which never banned travel by U.S. citizens) or by the entreaties of Myanmar activists, including Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, to avoid dealings which could help the military regime. Now that you can go, the question is why should you go. Quite simply, Myanmar is a beautiful, relatively unspoiled country, with friendly people and an amazing wealth of historic sites and natural beauty.

Our tour leaders, David Cardinal and myself, Edwin Reinke, have been travelling to Myanmar – often still called Burma by Westerners -- and leading tours there since 2005, and our experience has enabled us to pick the best spots…

An Overview of the History of Myanmar

At the risk of offending historians, this will be just a short overview of a long and at times very complicated history.

At the risk of offending historians, this will be just a short overview of a long and at times very complicated history.

Although there’s evidence of cultures along the Irrawaddy River as long as 13,000 years ago, Myanmar history really begins to take shape with a series of migrations. The Pyu entered what is now Northern Myanmar from southern China about 200 B.C. – dominating it until they were supplanted and assimilated by the Burmans, who arrive in the 9th century and finish absorbing the Pyu around the 12th century. Meanwhile, the Mon (who were Theravada Buddhists) migrated from what is modern-day Thailand and established themselves in the south and around the Irrawaddy delta.

Eventually the Kingdom of Pagan arose under Anawratha and effectively united what is most of modern Myanmar under the Burmans. Importantly, after conquering one of the Mon kingdoms, Anawratha established royal patronage of Theravada Buddhism and supported its introduction to Upper Burma. Unfortunately for the Kingdom of Pagan, the Mongols were on the move and sacked Pagan in 1287, ending this period of relative unity and ushering in a period of competing states which would last until the early 16th century with the rise of the Toungoo Empire.

After a series of setbacks delivered by the Mongols, the Mon, and the Shan states, Toungoo was just about the last kingdom still under Burman rule. However, under able and energetic leadership they had soon defeated their enemies and by the 1570s had established an empire constituting modern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, parts of the Tenasserim peninsula, parts of Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Manipur in India. This empire managed to hang on through various royal deaths, wars, and rebellions until 1752 when a resurgent Mon kingdom sacked the capital of Ava and put an end to the Toungoo Empire.

The Mons didn’t have a lot of time for self-congratulation, though, as a new Burman force, the Konbaung Dynasty arose, destroying the Mon army in 1759 and expelling the Mon’s foreign helpers, the British and French. Things stayed busy for the Konbaung Dynasty as they spent the next century warring with the Thais (six times!) and fending off four invasions from Qing Dynasty China. With expansion to the north and east cut off, the Konbaung turns west, conquering the Arakhan Empire (centered on Mrauk-U), Manipur (again), and Assam, which brought Burma right up against the British Empire.

Burma joins the British Empire

The British swallowed Burma in three chunks in the First, Second, and (yes, you guessed it) Third Anglo-Burmese Wars, which began in 1824 and finally ended in 1885 with the British in full possession of Burma and the last king, Thibaw, packed off to exile in India.

The British swallowed Burma in three chunks in the First, Second, and (yes, you guessed it) Third Anglo-Burmese Wars, which began in 1824 and finally ended in 1885 with the British in full possession of Burma and the last king, Thibaw, packed off to exile in India.

British rule proved to be no boon for Burma, as power and profits were reserved for the British themselves, the Anglo-Burmese, and Indian migrants, especially moneylenders who drove many Burmese landowners to penury. Consequently, by the 1920s revolutionary and independence movements had begun to form. When the Japanese invaded Burma in 1942, they found many willing allies among the Burmese (including national hero Aung San, father of Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi) who were looking to get rid of the British and who thought (wrongly) that Japan would allow Burma to become independent. Various other Burmese leaders – especially some of the minority tribal groups -- resisted the Japanese from the beginning and assisted the Allies. As the war turned against the Japanese the Burmese forces turned against the Japanese in May, 1945 and joined the Allies.

After the war the British attempted to hang on to control in the guise of facilitating reconstruction, but a series of strikes crippled those plans and Burmese independence was negotiated by Aung San and Clement Atlee January 27, 1947. Shortly thereafter Aung San concluded an agreement with ethnic minorities on February 12, which would be celebrated as Union Day. Burma had achieved its independence.

Major Sights of Myanmar

Yangon and the Shwedagon

Yangon, formerly Rangoon, Myanmar’s capital is home to over six million people and many opportunities for sightseeing and photography. Chief among these is the Shwedagon, one of Myanmar’s most important Buddhist sites.

Yangon, formerly Rangoon, Myanmar’s capital is home to over six million people and many opportunities for sightseeing and photography. Chief among these is the Shwedagon, one of Myanmar’s most important Buddhist sites.

Although the Shwedagon’s site has been used for religious purposes for more than a millennium, the Shwedagon as we now know it probably began to take shape in the 15th century (some Mon inscriptions from this period still exist at the current Shwedagon) with various additions following until the stupa assumed its current size and shape in the late 18th century. The Shwedagon takes its importance from its position as the repository of relics of the Buddha, in this case, hairs given by the Buddha to a legendary pair of Burmese brothers. Because of this, the Shwedagon has always been one of the major sites for Burmese Buddhists and Buddhist pilgrims from other countries.

The Shwedagon is no museum, but an active place of worship, playing host to a vast number of worshippers and tourists. Because of the practice of making merit, whereby a Buddhist can improve his or her karma by good deeds, acts, or thoughts, there is a constant stream of donations, great and small, and a continual process of renovation, restoration and new construction. These donations account for the estimated 75 tons of gold covering the stupa, as well as the outbuildings surrounding the stupa, which are of relatively recent (mid-19th century onward) vintage. The temple grounds abound with dozens, if not hundreds, of Buddha images where Buddhists can pay their respects, as well a series of “planetary posts”, altars and shrines representing the eight days of the traditional calendar (Wednesday is divided into two parts) where devotees bathe marble Buddha images with water and make other offerings. All this religious activity takes place in an atmosphere of friendliness and tolerance. Tourists and photographers are welcome.

Other than the Shwedagon, Yangon offers excellent opportunities to view and photograph everyday life in Myanmar. A trip to Yangon’s port area is always interesting, as one can see the sort of vessels that ply the Irrawaddy River (still a crucial artery for trade and travel) and watch them being loaded and unloaded by hand very much as they were a hundred years ago. A walk through Yangon’s Chinatown is also interesting to see, as one passes Chinese temples, outdoor butchers, and colonial British architecture. Finally, Bogyoke (Scott) Market has shops selling items of all descriptions, from everyday items for local people, to items for the tourist trade, gems and precious stones, antiques, and interesting textiles.

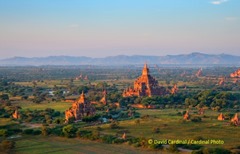

Bagan and the “Plain of Temples”

Bagan’s Archaeological Zone contains over 3000 recorded monuments in an area of roughly 13 by 7 kilometers. The majority of these are temples, stupas and monasteries. Although there are earlier structures like the Bupaya Pagoda (c.850, but destroyed by the 1975 earthquake and since reconstructed), building began in earnest in the 11th century and continued through the 13th century when Bagan was the capital, with over 900 temples, 500 stupas, and 400 monasteries being constructed. The pace slowed after the capital moved from Bagan to Ava, further north, in the 14th century, but building continued and at least 200 more monuments were built between the 15th century and today.

Bagan’s Archaeological Zone contains over 3000 recorded monuments in an area of roughly 13 by 7 kilometers. The majority of these are temples, stupas and monasteries. Although there are earlier structures like the Bupaya Pagoda (c.850, but destroyed by the 1975 earthquake and since reconstructed), building began in earnest in the 11th century and continued through the 13th century when Bagan was the capital, with over 900 temples, 500 stupas, and 400 monasteries being constructed. The pace slowed after the capital moved from Bagan to Ava, further north, in the 14th century, but building continued and at least 200 more monuments were built between the 15th century and today.

The monuments of Bagan can range from small, simple stupas to huge temples like Ananda, Nagayon, Thatbyinnyu, Sulamani, and Dhamma-yazika. It is estimated that 6 million bricks were required to build the largest temples, like the Dhamma-yazika. Depending on patronage and the availability of materials and labor, work could go relatively quickly, from seven and a half months for a medium sized temple to two years for the Dhamma-yazika. An interesting architectural point to notice in Bagan is the vaulting of the temples -- unprecedented in Asia at the time -- both lightweight and strong enough to support roof terraces and towers, for close to a thousand years in many cases.

N. B.: At this point it’s probably a good idea to clarify what is meant by a stupa, or a pagoda, or a temple. “Pagoda” can be a bit confusing, as it is used for both stupas and temples but we’re stuck with it in some cases due to its long usage. The stupa is a structure meant to be the repository of relics, whether of the Buddha himself, his disciples, or venerated monks. By and large stupas, or zedi in Burmese (similar to the word chedi in Thai) are bell-shaped. Temples, generally speaking, were built for the worship of Buddha images and usually feature an entrance hall leading to the sanctum where the Buddha image was placed.

Mandalay, Buddhist center of Myanmar

Mandalay and the surrounding area possess a wealth of sites for the visitor. Amarapura, Mingun, the U Bein Bridge, Kuthodaw, the Mahamuni Buddha, the Sagaing Hills, Ava, and Mandalay Hill are all easily accessible and well worth a visit.

Mandalay and the surrounding area possess a wealth of sites for the visitor. Amarapura, Mingun, the U Bein Bridge, Kuthodaw, the Mahamuni Buddha, the Sagaing Hills, Ava, and Mandalay Hill are all easily accessible and well worth a visit.

Sunsets at the U Bein Bridge and Mandalay Hill are outstanding photo opportunities. The U Bein Bridge is 1.2 kilometers long, crossing Taungthaman Lake and constructed largely of teak from an old palace (there have been some recent additions of concrete to add structural integrity). It is often claimed that the bridge is the longest teak bridge in the world, which seems odd until one actually sees it outlined against the sunset, monks and local residents crossing it or just enjoying the view. Likewise, sunset at Mandalay Hill can be quite lovely not only for the views over the surrounding area, but also for the play of the fading light upon the Sutaungpyei Temple at the summit (a modern addition).

Conveniently near are sites like the Kuthodaw or “world’s largest book,” and the Kyauk-Taw-Gyi temple. The Kuthodaw temple has the usual large golden stupa, but of greater interest are the 729 smaller white stupas, each containing a marble slab on which is incised part of the official canon of Theravada Buddhism. The Kyauk-Taw-Gyi at the foot of Mandalay Hill (not to be confused with similarly-named temples in Amarapura and Yangon) contains a 180-ton Buddha image, carved from a single block of marble.

Also in Mandalay itself is the beautiful and important Mahamuni Buddha image, one of the three great Buddhist sites in Myanmar (along with the Shwedagon and the Golden Rock). This bronze image was seized from Rakhine (the Arakhan Kingdom) and brought to Mandalay as a spoil of war. The image sees a constant flow of worshippers, many of whom line up to apply gold leaf to the body of the statue, which is encrusted to such an extent that its original form can only be guessed at. Male tourists and non-Buddhists are welcome to do this as well, and there is no prohibition on photography.

Nearby are Amarapura and Inwe where one can find the Bagaya Kyaung a monastery (formerly a palace) constructed from teak with very fine carvings on the exterior, some of which show a distinct European influence; another Kyauk-Taw-Gyi temple containing an important Buddha image and some of the best 19th century frescos in Myanmar; Myanmar’s own version of the “Leaning Tower”, the Namyin Watchtower, the only surviving piece of a palace built by King Bagyidaw; and the Maha Aungmye Bonzan, an impressive monastery built by Bagyidaw’s wife in 1818.

Nearby are Amarapura and Inwe where one can find the Bagaya Kyaung a monastery (formerly a palace) constructed from teak with very fine carvings on the exterior, some of which show a distinct European influence; another Kyauk-Taw-Gyi temple containing an important Buddha image and some of the best 19th century frescos in Myanmar; Myanmar’s own version of the “Leaning Tower”, the Namyin Watchtower, the only surviving piece of a palace built by King Bagyidaw; and the Maha Aungmye Bonzan, an impressive monastery built by Bagyidaw’s wife in 1818.

Further afield, a chartered boat ride takes us to Mingun, home of the huge uncompleted Mingun stupa, originally intended to be 150 meters tall, but discontinued (although some scholars posit that there were no actual plans for further construction) due to recognition of the project’s unfeasibility and/or on the grounds of predictions by court astrologers. In keeping with the massive size of the stupa is the world’s largest ringing bell, weighing 90 tons. A short walk away is the beautiful Hsinbyume, or Myatheindan Temple, the most sacred pilgrimage site in Mingun, which is built to represent Mount Meru, the center of the universe in Buddhist theology.

After all this history, a trip to the thriving riverside in Mandalay is a welcome change of pace. The workings of an up-country port and the people who live along the banks of the river are a mix of traditional trade and crafts with modern amendments. This visit is really extraordinary and rarely undertaken by other groups. It gives participants the chance to see some very hard-working people, some very poor indeed, go about their daily lives. These people have always been friendly and accepting of our visits, and one can get a real idea of what life can be like for people often thought of as living on the margins of society.

Kalaw, Pindaya Caves, and Inle Lake

After Mandalay, depending on our itinerary, we often head to the Shan State, where we typically stop in Kalaw, the Pindaya Caves, and at Inle Lake. The Shan are an ethnic minority who arrived in Burma with the Mongols and whose influence waxed and waned until they were finally overcome by the Burmans in the 1550s, though they retained a fair degree of autonomy thereafter. Their status as an ethnic minority, as well as a theoretical right of secession which is not recognized by the government, has led to inter-ethnic tensions as well as secessionist movements and Shans seeking refuge in nearby Thailand. Although there are continuing issues in parts of the Shan State, the areas we will visit are unaffected.

After Mandalay, depending on our itinerary, we often head to the Shan State, where we typically stop in Kalaw, the Pindaya Caves, and at Inle Lake. The Shan are an ethnic minority who arrived in Burma with the Mongols and whose influence waxed and waned until they were finally overcome by the Burmans in the 1550s, though they retained a fair degree of autonomy thereafter. Their status as an ethnic minority, as well as a theoretical right of secession which is not recognized by the government, has led to inter-ethnic tensions as well as secessionist movements and Shans seeking refuge in nearby Thailand. Although there are continuing issues in parts of the Shan State, the areas we will visit are unaffected.

Kalaw, where we stop first, is a pretty hill station and market town. As such it offers a different side of everyday life in Myanmar from some of the grittier urban or port-side settings. A very relaxing stop where even an arriving train offers a bewildering array of tribal costumes and slices of everyday life to photograph.

From Kalaw we pass through colorful farmland on our way to the amazing Pindaya caves. Inside the main cave are over 8000 Buddha images placed there from as far back as the 18th century. No other site in Myanmar has such a wide variety of images, including certain images associated with Mahayana Buddhism which are found nowhere else in the country. A truly fantastic, if challenging, photographic opportunity.

After the Pindaya Caves we head to Inle Lake, an area combining great natural beauty and traditional fishing villages dotted with traditional craftsmen happy to demonstrate their expertise.

From the itinerary of our Inle Lake visit:

The communities which make up the Inle Lake area live in and above water. Colorful fishing dugouts dot the Lake, singled out by the fishermen holding their seine nets, standing up while rowing with the oar wrapped around one leg. Schools, farms, shops, and homes alike round out the borders of the lake -- many supported on stilts or even floating.

The communities which make up the Inle Lake area live in and above water. Colorful fishing dugouts dot the Lake, singled out by the fishermen holding their seine nets, standing up while rowing with the oar wrapped around one leg. Schools, farms, shops, and homes alike round out the borders of the lake -- many supported on stilts or even floating.

Inle Lake is one of the world's richest fishing and farming regions, with luscious crops grown on man-made islands which can be moved around the lake by hand as needed. Children are often rowed to school, and goods are taken by boat to and from the picturesque "5-day" market -- which moves through a series of villages once every five days.

Indein, set back on a canal from the lake proper, is the Shan State version of Bagan. Over the centuries, victories were marked by new pagodas, yielding a now grass-entangled field of historic structures at the foot of a large staircase up to a temple with a view of the lake area.

Unique crafts are still practiced and practical in the Shan State. We'll see how dugouts and long-tail boats are made by hand, as well as the novel weaving of Lotus flowers into cloth. If we can do it without causing an ethical issue, we'll also get to see and photograph the dramatic brass-ring-necked Padaung women. And we'll certainly have opportunities to photograph the colorful Pa'O women with their distinctive orange head-dresses.

Sunrises and especially sunsets on the Lake are perfect times to capture fishermen both front and back-lit. Their triangle-shaped hats make perfect silhouettes in the sun. There are usually some other great photographs of family groups heading home from work and school. A one-of-a-kind collection of historic Shan thrones is also on display at the infamous "jumping cat" monastery -- where the cats are also happy to put on a show.

An optional extension to Western Burma -- For the adventurous

On some of our trips -- like the one scheduled for December, 2013 – we offer an optional extension to the less-explored region of Western Myanmar. Home of the ancient Arakhan Kingdom and its temples and crypts at Mrauk U, as well as the exotic Chin tribe, it is off the beaten path for most tourists, but still well-provisioned for an enjoyable experience.

Sittwe and Mrauk-U

Our optional extensions to Sittwe and Mrauk-U are exciting and fascinating trips. Sittwe is a pleasant bustling city on the southwest coast of Myanmar which has unfortunately been the scene of recent religious and ethnic clashes between Moslem Rohingyas and Buddhist Burmans. Obviously, no extension will be undertaken if there is any ongoing tension in the area.

Our optional extensions to Sittwe and Mrauk-U are exciting and fascinating trips. Sittwe is a pleasant bustling city on the southwest coast of Myanmar which has unfortunately been the scene of recent religious and ethnic clashes between Moslem Rohingyas and Buddhist Burmans. Obviously, no extension will be undertaken if there is any ongoing tension in the area.

Sittwe has a bustling port side market which is great for photos and, unusual for Myanmar, an Islamic element with several mosques. Reports are that the mosques may have been damaged recently, but one hopes that they will be restored by the time our visit takes place.

From Sittwe we take a chartered boat up the scenic Kaladan River, past jungle, plantations, temple, and riverfolk. Along the way we will see and be able to photograph boats of all sorts, and be able to observe trading and working in a part of Myanmar which few foreigners visit. With luck, we may see the rare, endangered Irrawaddy dolphin as we motor along.

In Mrauk-U we will see the remnants of the Arakan Empire which at its height stretched from Bengal to southern Burma and ruled the waters of the Bay of Bengal, maintaining a very active slave trade. Yet this was a Buddhist empire, building stupas and temples and revering the Mahamuni Buddha image which would eventually be seized by the Kobaung Empire in the north and installed in Mandalay.

The temples and stupas in Mrauk-U have their own character, similar but separate from those found elsewhere in Myanmar. Some, like Htu-kan-thein can appear almost forbidding. In addition to their powerful exteriors, most of the temples have crypts and corridors containing a vast number of Budddha images and bas-reliefs. One temple, Shit-thaung ,is referred to as the 80,000 images shrine. A flash and a tripod are helpful here for the photographer, and there are many interesting pictures waiting to be taken. One can get an even better view of the interior carvings and images at Koe-thaung, “the shrine of 90,000 images”, where subsidence and later excavation have opened some of the passages to the outside, enabling one to examine the intricate work in the light of day.

From Mrauk-U we head further up river to visit Chin villages, where women were given traditional facial tattoos, originally to make them less attractive to potential kidnappers, but as a sign of beauty and tribal tradition as time went on. The tattooed women are all older now, as the custom is dying out, so those who chose to accompany us on this extension will literally be witnessing the end of an era.

From Mrauk-U we head further up river to visit Chin villages, where women were given traditional facial tattoos, originally to make them less attractive to potential kidnappers, but as a sign of beauty and tribal tradition as time went on. The tattooed women are all older now, as the custom is dying out, so those who chose to accompany us on this extension will literally be witnessing the end of an era.

If you’d like to experience and photograph this amazing, and rapidly changing, country, we hope you can join us for our December, 2013 photo safari. We don’t have a final price yet, but if you want to make sure and hear when we do, please let us know by emailing safaris [at] cardinalphoto.com, or subscribe to our newsletter updates.

-- by Edwin Reinke, long-time SE Asia resident, freelance writer, and Cardinal Photo co-lead

- Log in to post comments